Key Points

-

The banking system is the main channel through which monetary policy impacts the economy. Higher interest rates over the past year have negatively impacted lending and banking profits which increases bank funding costs and can lead to weaknesses in specific organisations with existing vulnerabilities (like overexposure to lending in a specific industry) which explains the collapse in some regional US banks.

-

The banking sector is critical to the economy as a source of stability and confidence. While banks are in a stronger position compared to the GFC period, a banking crisis is still possible and risks having a larger chain reaction to the rest of the economy through a decline in customer deposits, falling bank liquidity, negative wealth effects for investors and tighter credit standards and financial conditions reducing lending and economic growth.

-

The banking crisis is a perverse sign that monetary policy is working and may work to slow the pace of further interest rate increases from central banks.

Introduction

A well-functioning and stable banking system is central to the proper functioning of an economy. The recent banking crisis which has impacted regional lenders in the US and Europe’s Credit Suisse Bank highlights the risk to the banking sector from the rise in interest rates over the past year, as banking is one of the most interest-rate sensitive parts of an economy. In this Econosights we look at the role of the banking sector in an economy and how the recent developments risk a further negative flow-on impact to the rest of the economy.

The role of the banking sector

Finance and insurance makes up 7.3% of GDP in Australia, 7.8% of GDP in the US and a smaller 4.3% in the Eurozone. In terms of employment, finance and insurance makes up 4% of jobs in Australia, 5.9% in the US and 1.4% in the Eurozone. These proportions seem fairly modest but underestimate the importance of the banking sector as a lending and depository intermediary in the economy.

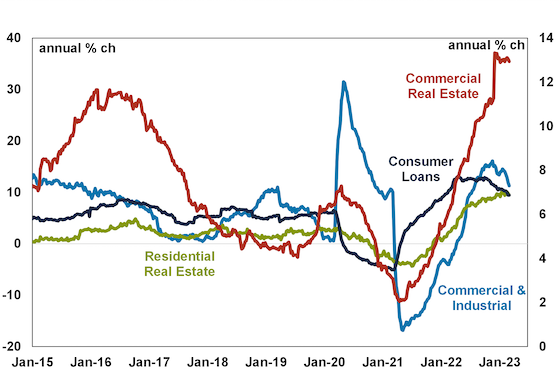

Banking is directly impacted by monetary policy changes through the lending channel. When monetary policy is tightened (interest rates rise and/or the central bank reduces the size of its balance sheet) lending growth slows because the cost of borrowing rises and when monetary policy is loosened (interest rates are cut and or the central bank expands its balance sheet) then lending growth tends to rise because the cost of borrowing falls. Given the tightening in monetary conditions since early 2022, US lending growth has started slowing in the past few months, especially for commercial and industrial loans (see the chart below).

US Loans & Leases

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

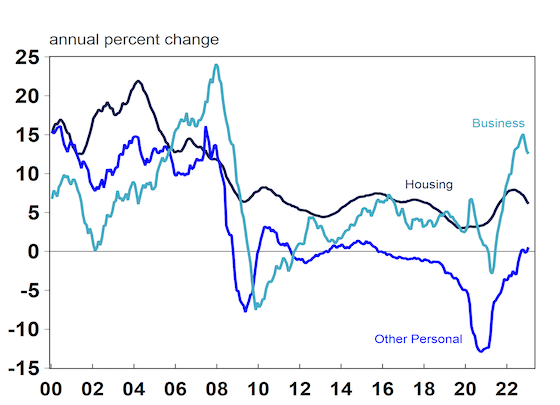

Similarly in Australia, credit growth has been turning down for housing since mid 2022, business lending has been stronger but has slowed and other personal credit is roughly flat.

Australia Crdit Growth

Source: Macrobond, AMP

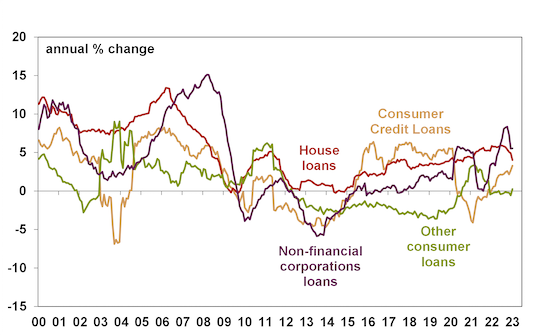

And in the Eurozone, corporate and housing loan growth has been slowing in recent months (see the chart below).

Eurozone lending

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

So, the current banking crisis is occurring against the backdrop of already slowing credit growth.

Impacts of the current banking crisis to the rest of the economy

In recent weeks, three regional US banks have collapsed (Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and Silvergate Corporation), US-based First Republic Bank needed a USD $30bn cash injection by the major banks to stay afloat and Europe’s Credit Suisse Bank has been bought over by rival UBS. This has been the worst period for the banking sector since the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. Policymakers have tried to stem deposit outflows and restore confidence to minimise the damage to the sector, with the US government guaranteeing deposits over $250,000 (the government always guarantees or insures deposits under $250,000) at the impacted banks, providing a cheap lending facility to the banks (via the Bank Term Finding Program offering loans up to a year, worth up to $25bn which will mean an expansion of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet) and the Swiss National Bank offered a CHF 50bn loan to Credit Suisse.

These recent issues in the banking sector reflect individual problems with these institution’s (including improper risk management like the overexposure to duration risk by Silicon Valley Bank and the concentration of lending and deposits to the tech sector) but were exacerbated by the increase in interest rates over the past year which has lifted funding costs for banks and decreased lending activity (which is negative for banking profits). The risk is that the tightening in monetary conditions will expose fragilities across more of the banking sector, despite a tightening in regulation since the GFC and high capital buffers.

There are multiple ways that a further weakening in the banking sector could flow through to the broader economy including:

-

A decline in customer deposits leading to a “bank run” if customers loose confidence in the banking system, especially for smaller lenders which is where the problems seem to be based at the moment in the US.

-

A rise in bank funding costs which gets passed through to households (a de facto increase in interest rates).

-

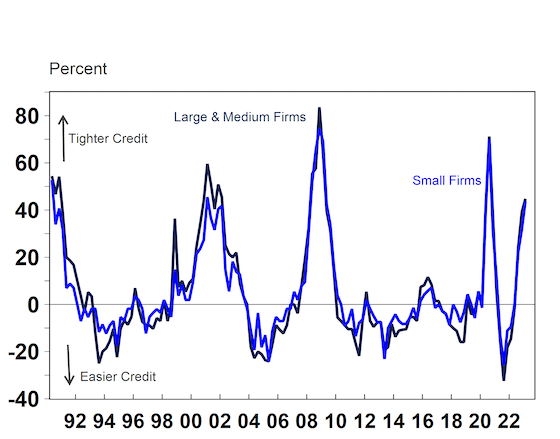

A further tightening in lending standards (also a de facto increase in interest rate) which limits lending growth to businesses and households. Lending standards had already become tighter in recent months, before the banking crisis started (see the chart below).

US Commercial & Industrial Lending Standards

(Net % of domestic banks tightening standards)

Source: Macrobond, AMP

-

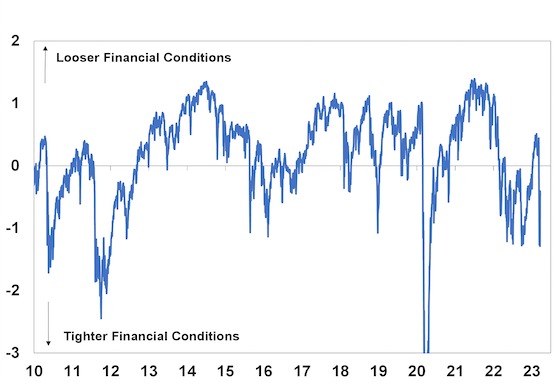

A further tightening in financial conditions (which is an overall measure of financial stress and takes into account credit treasury rates, credit spreads, volatility, level of the sharemarket). Financial conditions have tightened since the crisis started, but not to overly restrictive levels yet (see the chart below).

US Bloomberg Fiancial Conditions

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

-

Negative wealth effects through a loss for investors if individual share prices decline (there have been large falls in US regional bank share prices), a broader market deterioration if share markets fall significantly or a loss on other products like the issues with the UBS Additional Tier 1 bonds, which were not expected to loose all of their value (although regulators have indicated that this was likely to be a one-off loss in AT1 bonds and should not be replicated for other banks).

Impacts of the banking crisis on central banks

The risks to financial stability through the banking sector issues mean that fewer interest rate hikes from central banks should be expected in the near-term. While inflation is still elevated in the major economies, the tightening in financial conditions and lending standards will weigh on economic growth and help to put downward pressure on inflation. Along with other indicators of slowing inflation including large declines in commodity prices and declining producer price inflation, inflation in the major economies should continue to trend down over 2023. This means that we are likely close to the end of the hiking cycle for the major central banks.

Conclusion

The banking sector as a whole looks fundamentally stronger compared to the GFC because of better and tighter regulation however it is probably too soon to be confident that the situation in the banking sector has completely resolved itself, given the vulnerability of the sector to higher interest rates. Banks make up a decent proportion of sharemarket indices, at a hefty 30% of the Australian ASX200, 13% of the US S&P500 and 9% of the Eurozone STOXX50. While Australian banks have not been impacted directly by the recent issues in the US and Eurozone, any decline in confidence around the strength of the banks could still weigh on bank stocks, which will impact the wider market.

However, an earlier pause to central bank rate hikes due to the situation in the global banking sector could be a positive for sharemarkets if the situation in the banking sector stabilises, which in turn could provide an opportunity for some investors. In our view, most central banks are close to the top of their rate hike cycle. We see the Reserve Bank of Australia keeping the cash rate unchanged at 3.6% at the April Board meeting. The US Federal Reserve is likely to hike the Fed Funds rate again at its next meeting in May before keeping interest rates on hold.

Source: AMP March 2023

Important:

This information is provided by AMP Life Limited. It is general information only and hasn’t taken your circumstances into account. It’s important to consider your particular circumstances and the relevant Product Disclosure Statement or Terms and Conditions, available by calling PH: 0437 782 836, before deciding what’s right for you.

All information in this article is subject to change without notice. Although the information is from sources considered reliable, AMP and our company do not guarantee that it is accurate or complete. You should not rely upon it and should seek professional advice before making any financial decision. Except where liability under any statute cannot be excluded, AMP and our company do not accept any liability for any resulting loss or damage of the reader or any other person. Any links have been provided for information purposes only and will take you to external websites. Note: Our company does not endorse and is not responsible for the accuracy of the contents/information contained within the linked site(s) accessible from this page.